![]()

ONLINE

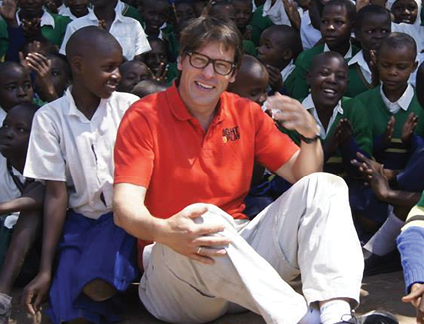

Johann Olav Koss in Tanzania

The Right To Play

Editors’ Note

Johann Koss first became involved with Right To Play (then known as Olympic Aid) in 1993 after visiting the African country of Eritrea. The four-time Olympic Gold Medalist made international headlines when he won three Gold Medals at the 1994 Lillehammer Games in the 1,500-, 5,000-, and 10,000-metre speed-skating events. Following his 1,500m, he promptly donated the prize money to Olympic Aid and challenged his fellow citizens to donate 10 Norwegian kroner for each gold medal won by Norway. Outside of his role as President and CEO of Right To Play, Koss has also served as a founding board and executive board member of the World Anti-Doping Agency, where he initiated the Athlete anti-doping passport. In 1994, he was appointed Special Representative for Sports for UNICEF International. Koss was declared “One of 100 Future Leaders of Tomorrow” by TIME Magazine, and “One of 1,000 Global Leaders” by the World Economic Forum. He completed his undergraduate medical training at the University of Queensland, and his executive M.B.A. at the Joseph L. Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto. In June 2005, Koss received a Doctor of Laws Honorary Degree from Brock University, and in 2009, he received a second Doctor of Laws Honorary Degree from the University of Calgary, and an Honorary Doctorate from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, in Belgium in 2011. In January 2006, the World Economic Forum named Johann a Young Global Leader. Most recently, he received Ernst & Young’s Entrepreneur Of The Year Special Citation award for social entrepreneurship.

Organization Brief

The mission for Right To Play (righttoplay.com) is to use sport and play to educate and empower children and youth to overcome the effects of poverty, conflict, and disease in disadvantaged communities.

How did Right To Play come about?

The key was my personal experience traveling around the world, particularly in war-torn regions and areas of poverty. I took for granted access to play in a sport program when I grew up – we had a safe place to go.

If you want to rebuild civil society and create safe places for people to harness their talent and learn to believe in themselves and give back to their communities, they need that space.

At the end of the 1990s, I tried to get the UN agencies and International Olympic Committee to recognize that we have forgotten this major factor in building successful societies. They insisted that this need is a luxury.

I realized I had to improve the concept so people would see the need and start to build to scale. It required a high-scale program that was extremely cost effective with a low cost per participant and that was very strong both in the development of individuals and their societies.

Right To Play programming

in action in China

How did you build the critical relationships to ensure you would create the impact you desired?

We started with young college graduates who interned and started initiating activities for the children. Soon, every time we brought the Right To Play car or t-shirts to a community, the kids knew what it was and wanted to participate.

The parents then came to see what was happening and, as we grew, we found that we needed to recruit local people who had a passion for how sport can affect children to train them. We built our internal support within those communities for the people that were there to run the programs.

There are still coaches in refugee camps in certain countries that have been with our organization since we started in 2001. They are volunteers who work every week providing activities for 30 to 150 kids.

How has the program expanded internationally?

The Middle East is a critical area for us. We started there around 2003 when we partnered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) to offer our program to Palestinian refugees. We expanded from there into the local communities where we did our camps. We operated throughout the fighting there during the 2006 war with Israel and then with Lebanon.

We have grown in Pakistan. When everybody was pulling out, we went in to help Afghani refugees who were there because of the Afghani war.

We also expanded into Pakistani communities. Today, we have more than 165,000 kids in Pakistan in our program and over 50 percent of them are girls. The programs are all run by our Pakistani staff who have been trained and are extremely well-educated, both in the schools and outside.

In Thailand, there are some five camps, which also include educational efforts. We started expanding the schools in the south after the tsunami. It has gained a high level of trust from the Thai government, through the School Excellence initiative, which all the centers are building up in Thailand.

So what you’re providing is much broader than just sport?

Much broader. Sport and play are tools; what we’re achieving is improved education. Attendance rates have gone straight through the roof; we see academic performance improving dramatically; teacher/child relationships are also much better; and the environment within the schools is improving.

We’re building societies through community organizations, and diverse groups of people in the communities are coming together to overcome differences. We bring people out to talk about child protection rights, gender equality, and health issues like clean water. The program inherently has a convening power.

How do you work in these countries to create a sustainable model?

It requires that we set up programs that are locally run by local people supported by local money.

First, people need to feel this is important for the children. I still have difficulty finding a child who doesn’t want to play – they just don’t know they have the right to do it. So you need to create that tipping point.

Then you need to influence government policy because once you reach that tipping point, you can create legislation. So the policy is formed in the government and it then requires funding. For some of these countries, it will take a long time before there are sufficient financial resources to support what is needed.

If we create the tipping point, manage to build the right legislation, and the government starts channeling funding towards these programs through the local people who are trained and educated, we will create a sustainable model.

What will it take to be able to expand your reach?

We are so small – and there are young kids running around camps right now, throwing stones at each other and creating gangs, and forming rebel groups.

To stop that, you need to get them playing sports on the playground. It’s pretty simple, but you have to be there – and you need money to do it.•